Skulls

The Mexican Skull or Calavera is a classic object of the Day of the Dead or Dia de Muertos of Mexico and is part local crafts. These skulls, which are found on altars of the dead, are considered the essential part of the body of the deceased. They brighten up with their color and the finesse of their manufacture and thus chase away the sadness that can arise when remembering missing people. They are thus, in Mexico, largely associated with life and not with death. This is why on Day of the Dead, Mexicans dress up as a skeleton or skull’s head and party while doing their offerings for their dearly departed.

The talented artists and craftsmen of Mexico who design and make the heads of the dead give free rein to their imagination to make skulls or skulls a unique work.

Sugar skulls or calaveras de alfeñique are also very present among all Mexican skulls.

🔍 Discover our offer—and find all the information about the Mexican skull at the bottom of the page.

Showing all 12 results

-

Sugar Skull #5

6,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Eternal Love Lesbians

22,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Straight Eternal Love

22,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Gay Eternal Love

22,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Vanity Candle holder

49,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Vanity Candle holder

49,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Gay love showcase

49,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Straight love showcase

49,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Showcase offering to Lupe

24,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

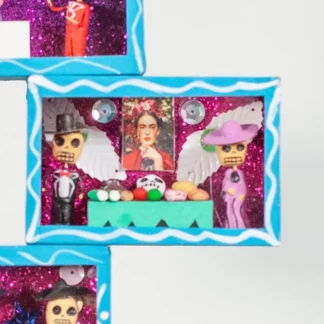

Frida offering display case

24,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Turquoise display Tacos

24,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart -

Lesbian love showcase

49,00 € inc. VAT Add to cart

Showing all 12 results

The Mexican skull

The “Mexican skull” (or calavera) is far more than a mere macabre motif: it’s a vivid manifesto celebrating life and memory. Hand-painted on ceramics, molded in sugar, carved from wood or fashioned into jewelry, these skulls don bright hues—fuchsia pink, brilliant turquoise, sun-yellow—adorned with flowers, arabesques and geometric patterns. Each one asserts its identity: floral motifs pay tribute to nature; a small cross on the brow recalls the spiritual dimension; dots or rhinestones lend a festive flair. Beyond mere decoration, the Mexican skull embodies resilience in the face of death, reminding us that bonds of affection endure and that the memory of the departed lives on through ritual and shared moments.

Origins of Mexico’s Death-Celebration Tradition

- Mexico’s Day of the Dead springs from a syncretism between pre-Hispanic rites (Aztec, Toltec and Maya) and the Catholic observances introduced by Spanish colonizers in the 16ᵗʰ century.

Pre-Columbian rituals: Ancient civilizations venerated their ancestors, offering fruits, flowers and tortillas to accompany souls into the afterlife. Death was seen as a transitional phase, not a final end. - Syncretism: When indigenous rites were prohibited, the Spanish imposed All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day (November 1–2). Local populations merged these with their own customs, preserving the spirit of offerings, processions and vigils while adapting dates.

Popularized worldwide in the 2000s by its joyful, colorful iconography, Mexico’s Day of the Dead remains deeply rooted at home, oscillating between cemetery remembrances and festive street celebrations—and it has since spread to many other countries.

Local Expressions of the Mexican Skull

Calaveras appear in multiple materials and contexts:

- Sugar skulls (calaveras de azúcar): Small, edible molds of cooked sugar, decorated with tinted icing. Given to friends and children, often personalized with the name of a deceased loved one.

- Cartonería (papier-mâché): Lightweight, elaborately crafted skulls—used as piñatas, giant procession puppets (“mojigangas”) or street decorations.

- Ceramics and terracotta: Hand-painted statuettes and offering boxes for home altars, ranging from naïve folk-art to finely detailed realism.

- Textiles and apparel: T-shirts, embroidered scarves and tablecloths bearing calavera motifs, plus masks for traditional dances—most famously the horned “Diablos de Huehue,” blending skull and devilish horns.

The Day of the Dead Celebration

Observed over two days—November 1 and 2—the festival distinguishes between “little dead” and “great dead”:

November 1 (“Día de los Angelitos”): Honors deceased children. Families build part of the altar with toys, sweet bread (“pan de muerto”) and yellow marigolds to welcome the souls of infants.

November 2: Pays tribute to adult ancestors. Altars swell with the departed’s favorite foods, fruits, beverages (tea, mezcal) and symbolic objects.

Each ofrenda (altar) comprises seven essentials: photographs, candles, calaveras, marigolds (cempasúchil), incense, water and food. Families dress in traditional attire, clean and decorate tombs, and keep vigil all night with music and shared offerings. This dual rhythm—intimate remembrance and exuberant festivity—makes Mexico’s Day of the Dead a singular moment when life is joyfully celebrated through death.